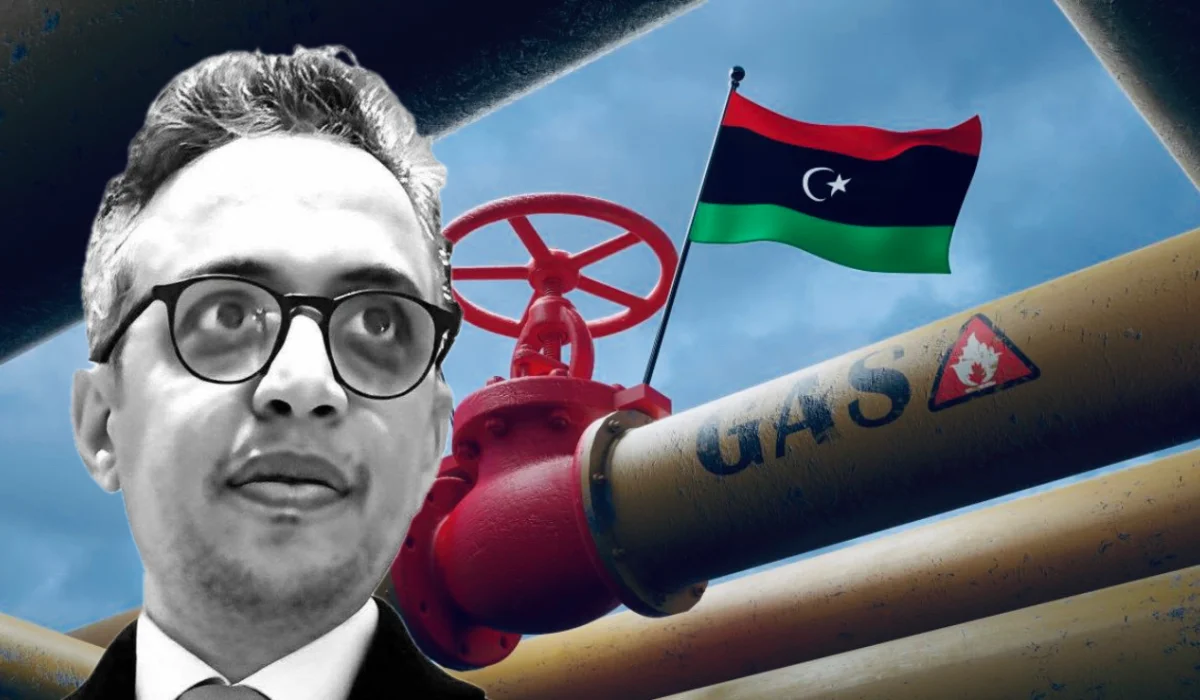

Ahmed Zaher wrote an article entitled: “Libya and the Curse of Oil – When the Economy Devours Society“:

Great wealth doesn’t always produce great nations; sometimes, it yields even greater corruption—because when abundance precedes awareness, it turns from a blessing into a curse.

When Libya transitioned from a feudal system to capitalism, the consequences of this shift were not addressed in a manner fitting its depth and gravity. The country opened up to a market economy without institutional infrastructure, a mature middle class, or a stable production culture.

Traditional social structures—based on kinship, land, and manual labor—still dominated society, while money began flowing from outside, not from within the cycle of production. This created a profound imbalance between the emerging economic structure and the outdated social reality lagging behind it.

The discovery of oil in the 1950s marked a turning point—not only economically, but socially and philosophically. It provided the state with massive resources without the need for production or taxation, collapsing the contractual relationship between state and society. A pure rentier state was born, based on distribution rather than production, and loyalty rather than efficiency. Oil was not merely a wealth source—it was a new “political entity” that transformed the shape, functions, and social boundaries of the state.

Before oil, land was the economic and social center of gravity. Owners of fertile land, major farmers, and tax officials held the upper hand because they controlled sources of livelihood and fed the state treasury. But oil overturned this balance.

The state no longer derived its resources from society; instead, it began distributing rent to it. The citizen transformed from a producer to a beneficiary, from an economic partner to a rent-dependent follower. The influence and social roles of farmers and landowners eroded, and parasitic classes emerged suddenly in cities—living off public employment, government contracts, or rent-based privileges, without real contribution to development.

Libya thus became a rentier society before its economic structure had fully formed. It never experienced an industrial phase, lacked a mature working class, and never saw productive capitalism. The modern state took on a capitalist form in its tools and institutions but was hollowed out of the market’s logic and equilibrium—leaving the Libyan economy prone to distortion and regression, unable to build stable classes or natural production relationships.

In this fragile context, Colonel Muammar Gaddafi attempted to build a “socialist” project based on an inverted Marxist logic. He assumed that transitioning to socialism was the natural next step after capitalism—without realizing that Libya hadn’t yet experienced capitalism itself. The country had just emerged from feudalism and lived off underground rent, not labor. Yet Gaddafi forced an ideological leap forward.

Thus, the socialist shift resembled an escape forward. Gaddafi ignored the wounds inflicted by the oil and social transformation and layered a new crisis on top by pushing for socialism in one go—without societal readiness or time for political and economic maturity. The result was a premature birth of a deformed entity: neither capitalist nor socialist, but a hybrid creature—confused and disjointed, incapable of normal life or swift death.

Despite the obvious flaws, Gaddafi persisted in trying to “resuscitate the fetus.” He built superficial institutions, funneled state resources into theoretical slogans, and produced rhetoric detached from reality. The socialism he promoted was merely ideological mobilization layered atop a rentier economy governed by clientelism and distribution—not by planning or production. Thus, the dying body remained on life support for decades until it entered clinical death, then total collapse in 2011.

But the tragedy is that the “curse of oil” did not end with the fall of the regime. After the revolution, the Libyan state continued the same rentier model: distributing resources, buying loyalties, unproductive public employment, a fragile economy dependent on global fluctuations, and a society decaying from within due to a loss of purpose and work. Oil rent transformed from a tool of power into a tool of chaos, with each faction seeking to capture it—not to build a shared national economy.

Today, we don’t need to attempt to revive the corpse of old rent, nor to cling to repackaged socialist or liberal illusions.

We need a rebirth—one grounded in a deep understanding of our trajectory, in radical social critique of the transformations that shook us, and in economic planning that’s not just about diversifying resources, but about reshaping the relationship between citizen and state, between labor and dignity, between wealth and justice.

The curse of oil cannot be resolved merely through management—it must be transcended altogether: by building a state with a productive project, a society capable of work—not waiting, and institutions that enforce contractual—not paternal—relations.

Without that, we will continue to live in the spiral of “rent and waiting,” where production is replaced by loyalty, development by bargaining, and the state by its shadow.

Libya will not recover from the curse of oil until it moves beyond the illusion of wealth to the truth of work, and abandons the state that distributes—to build the state that produces.